- Home

- Rick R. Reed

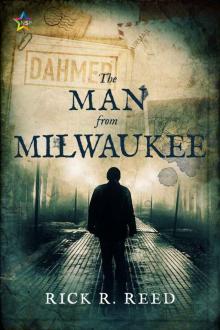

The Man From Milwaukee

The Man From Milwaukee Read online

A NineStar Press Publication

www.ninestarpress.com

The Man from Milwaukee

ISBN: 978-1-64890-044-0

Copyright © 2020 by Rick R. Reed

Cover Art by Natasha Snow Copyright © 2020

Published in July, 2020 by NineStar Press, New Mexico, USA.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form, whether by printing, photocopying, scanning or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact NineStar Press at [email protected].

Also available in Print, ISBN: 978-1-64890-045-7

Warning: This book contains sexually explicit content, which may only be suitable for mature readers, deceased family member, kidnapping, violence/gore, attempted murder, and death of a parent.

The Man from Milwaukee

Rick R. Reed

Table of Contents

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

About the Author

For those readers who’ve been with me since my horror beginnings—this one’s for you.

He learned only in bits and pieces of that wonderful blossoming of dark and lovely flowers: one was revealed to me by a scrap of newspaper…

—Jean Genet, Our Lady of the Flowers

I had these obsessive desires and thoughts wanting to control them to–I don't know how to put it–possess them permanently.

—Jeffrey Dahmer

Monsters are real, and ghosts are real too. They live inside us, and sometimes, they win.

—Stephen King

Part One

Summer

Chapter One

HEADLINES

Dahmer appeared before you in a five o'clock edition, stubbled dumb countenance surrounded by the crispness of a white shirt with pale-blue stripes. His handsome face, multiplied by the presses, swept down upon Chicago and all of America, to the depths of the most out-of-the-way villages, in castles and cabins, revealing to the mirthless bourgeois that their daily lives are grazed by enchanting murderers, cunningly elevated to their sleep, which they will cross by some back stairway that has abetted them by not creaking. Beneath his picture burst the dawn of his crimes: details too horrific to be credible in a novel of horror: tales of cannibalism, sexual perversity, and agonizing death, all bespeaking his secret history and preparing his future glory.

Emory Hughes stared at the picture of Jeffrey Dahmer on the front page of the Chicago Tribune, the man in Milwaukee who had confessed to “drugging and strangling his victims, then dismembering them.” The picture was grainy, showing a young man who looked timid and tired. Not someone you'd expect to be a serial killer.

Emory took in the details as the L swung around a bend: lank pale hair, looking dirty and as if someone had taken a comb to it just before the photograph was snapped, heavy eyelids, the smirk, as if Dahmer had no understanding of what was happening to him, blinded suddenly by notoriety, the stubble, at least three days old, growing on his face. Emory even noticed the way a small curl topped his shirt's white collar. The L twisted, suddenly a ride from Six Flags, and Emory almost dropped the newspaper, clutching for the metal pole to keep from falling. The train's dizzying pace, taking the curves too fast, made Emory's stomach churn.

Or was it the details of the story that were making the nausea in him grow and blossom? Details like how Dahmer had boiled some of his victim's skulls to preserve them…

Milwaukee Medical Examiner Jeffrey Jentzen said authorities had recovered five full skeletons from Dahmer's apartment and partial remains of six others. They’d discovered four severed heads in his kitchen. Emory read that the killer had also admitted to cannibalism.

“Sick, huh?” Emory jumped at a voice behind him. A pudgy man, face florid with sweat and heat, pressed close. The bulge of the man's stomach nudged against the small of Emory's back.

Emory hugged the newspaper to his chest, wishing there was somewhere else he could go. But the L at rush hour was crowded with commuters, moist from the heat, wearing identical expressions of boredom.

“Hard to believe some of the things that guy did.” The man continued, undaunted by Emory's refusal to meet his eyes. “He’s a queer. They all want to give the queers special privileges and act like there’s nothing wrong with them. And then look what happens.” The guy snorted. “Nothing wrong with them…right.”

Emory wished the man would move away. The sour odor of the man's sweat mingled with cheap cologne, something like Old Spice.

Hadn't his father worn Old Spice?

Emory gripped the pole until his knuckles whitened, staring down at the newspaper he had found abandoned on a seat at the Belmont stop. Maybe if he sees I'm reading, he'll shut up. Every time the man spoke, his accent broad and twangy, his voice nasal, Emory felt like someone was raking a metal-toothed comb across the soft pink surface of his brain.

Neighbors had complained off and on for more than a year about a putrid stench from Dahmer's apartment. He told them his refrigerator was broken and meat in it had spoiled. Others reported hearing hand and power saws buzzing in the apartment at odd hours.

“Yeah, this guy Dahmer… You hear what he did to some of these guys?”

Emory turned at last. He was trembling, and the muscles in his jaw clenched and unclenched. He knew his voice was coming out high, and that because of this, the man might think he was queer, but he had to make him stop.

“Listen, sir, I really have no use for your opinions. I ask you now, very sincerely, to let me be so that I might finish reading my newspaper.”

The guy sucked in some air. “Yeah, sure,” he mumbled.

Emory looked down once more at the picture of Dahmer, trying to delve into the dots that made up the serial killer's eyes. Perhaps somewhere in the dark orbs, he could find evidence of madness. Perhaps the pixels would coalesce to explain the atrocities this bland-looking young man had perpetrated, the pain and suffering he’d caused.

To what end?

“Granville next. Granville will be the next stop.” The voice, garbled and cloaked in static, alerted Emory that his stop was coming up.

As the train slowed, Emory let the newspaper, never really his own, slip from his fingers. The train stopped with a lurch, and Emory looked out at the familiar green sign reading Granville. With the back of his hand, he wiped the sweat from his brow and prepared to step off the train.

Then an image assailed him: Dahmer's face, lying on the brown, grimy floor of the L, being trampled.

Emory turned back, bumping into commuters who were trying to get off the train, and stooped to snatch the newspaper up from the gritty floor.

Tenderly, he brushed dirt from Dahmer's picture and stuck the newspaper under his arm.

*

> Kenmore Avenue sagged under the weight of the humidity as Emory trudged home, white cotton shirt sticking to his back, face moist. At the end of the block, a Loyola University building stood sentinel—gray and solid against a wilted sky devoid of color, sucking in July’s heat and moisture like a sponge.

Emory fitted his key into the lock of the redbrick high-rise he shared with his mother and sister, Mary Helen. Behind him, a car grumbled by, muffler dragging, transmission moaning. A group of four children, Hispanic complexions darkened even more by the sun, quarreled as one of them held a huge red ball under his arm protectively.

As always, the vestibule smelled of garlic and cooking cabbage, and as always, Emory wondered from which apartment these smells, grown stale over the years he and his family had lived in the building, had originally emanated.

In the mailbox was a booklet of coupons from Jewel, a Commonwealth Edison bill, and a newsletter from Test Positive Aware. Emory shoved the mail under his arm and headed up the creaking stairs to the third floor.

*

Mary Helen waited.

A cloud of blue cigarette smoke hung near the ceiling, ethereal. The smoke didn't cover the perfume Mary Helen wore, something called Passion. She had doused so much of it on herself that Emory wanted to cover his nose, to gag, to ask her if she was in her right mind.

But he said nothing, only smiled at his younger sister, who sat, long legs thrown over the arms of a brown corduroy recliner, staring dumbly at the screen. The flickering images of a sitcom made Mary Helen's face alternately light and then dark. Canned laughter erupted every few moments, and Emory prickled. He felt as though they were laughing at him.

He cleared his throat, hoping his sister would notice him. There was a time, not so long ago, when he, a fifteen-year-old boy, and she, a little towheaded girl of seven, would sprawl on the living room floor together, newspapers spread out in front of them, and share a box of powdered sugar doughnuts while watching TV together.

Those days were long past. Mary Helen had dropped out of high school in the spring and now seemed to have no occupation other than sitting around the apartment during the day and disappearing to God knows where at night, sometimes not returning until the early morning, when dawn’s gray light worked its transformation on the apartment, giving the worn furniture and threadbare carpets definition and color.

“Hello, Mary Helen,” Emory moved toward the TV screen. “What are you watching?” A little girl on the television was dramatically rolling her eyes as an older man explained the virtues of telling the truth.

Mary Helen shifted in her seat, put her feet on the floor. She grabbed the remote control from the end table beside her and banished the father and daughter to darkness.

“Nothin’.” She lit another cigarette from the butt of the last. She blew a stream of smoke toward her brother.

Emory waved the smoke away. “Have you had anything to eat?”

She glared at him, pursing her lips together. “No. Have you?”

Emory put his briefcase on a spare chair in the dining room, loosened his tie. There was a fan blowing, and Emory stood in front of it. The fan delivered no relief; it merely blew the hot air around more intensely.

“How was Mother today?”

Mary Helen stood and examined a run in the back of her black stockings. “Shit,” she whispered to herself, then looked up at her brother. She smiled and her eyes sparkled. For a moment, Emory smiled back, startled to see a return of the cheerful little girl who used to live here.

“Mother had a complete recovery today. In fact, she’s not even in her room. She got up around ten, dressed herself in a pink linen dress—charming little chapeau with a veil, stockings, the whole nine yards. She then went down to the L station. Told me she was headed downtown, to fucking Marshall Fields, where she'd do a little shopping and have lunch in the Walnut Room. And then she was going over to Thirty Three Personnel on Dearborn to see if they had anything in her line…” Mary Helen took a deep drag on her cigarette and blew the smoke once more at her brother, shaking her head. “How the fuck do you think she is?”

Emory licked his lips and rubbed his hands together. His palms were sweating.

Mary Helen started toward the door. She wore a black miniskirt and a black leather vest under which was a sheer black-lace body shirt. She had dyed her hair platinum blonde and cut it so that it stood up in hard little spikes. She wore silver hoop earrings, rows of four in descending size, in each ear. Her nose sported a silver stud. Emory wondered what was to be pierced next but could never ask her. She had done her face up to make it paler than it already was and lined her eyes in thick black mascara.

“Did Mother eat anything today?” Emory called after her.

Mary Helen replied by closing the front door softly.

“Does Mother need anything?” he asked the closed door.

*

Emory paused, hand on the brass-plated doorknob to his mother’s room, wishing he could have just one day when he wouldn’t have to go inside. But who would take care of Mother if he didn’t? Mary Helen never went into their mother's room during the day, even though she was supposed to be at home to take care of her.

Emory wondered how smoking cigarettes and watching talk shows on TV all day qualified as caregiving, then chastised himself for thinking so unkindly of his younger sister.

Emory gripped the doorknob tighter and turned it slowly, wondering if this would be the day he’d open the door and find his mother dead. As he leaned on the door, letting his weight open it, he pictured her, glazed blue eyes staring up at the ceiling, body stiff and cold.

He despised himself for the thought that rushed forward—he’d be relieved. He paused for a moment at the entrance to his mother’s room and noted how it was a shrine to both her dying and her life and the vitality that AIDS had drained from her. Her art was the only living thing in the room.

Back in the days before she was sick, Mother indulged her creative tendencies by taking pottery classes, and the room was a testament to her handiwork. She had talent, Emory had always thought. There was something ethereal about the small vases and whimsical figurines she crafted. They had a fairylike delicacy, enhanced by the bold colors Mother used to glaze them—cobalt blue, orange, crimson, chromium yellow, and black. Her masterwork, a gangly gargoyle, stood guard on the nightstand next to her bed, it’s bloodshot aquamarine eyes staring away intruders. There was barely room for the figure, some twelve inches tall and heavy, on the table’s top, crowded as it was with prescription bottles, water, and Mother’s inhaler.

Emory sighed for all that had been lost so quickly and completely.

The room reeked of feces and urine, the odor hanging over it like Mary Helen’s cigarette smoke in the living room. The smell rushed out, an assailant. Emory choked back a gag. The same scent greeted him every weekday upon his return home from work, and yet he never got used to it. It never failed to cause the bile to rise, burning the back of his throat.

Mother lay, head propped up on three pillows, staring vacantly ahead. If she noticed that Emory had come into the room, no sign registered in her eyes.

Mother was naked. Emory tenderly picked up the balled-up cotton nightgown at the foot of the bed, squeezing and releasing its soft, quilted nap with trembling fingers.

Perhaps if I just step back and quietly leave the room, she won’t notice me standing here. Maybe if we just left her alone for a few days without care, she could let go, leave, and then she would be at peace.

And so would I.

Emory dropped the nightgown and bit the inside of his mouth hard enough to taste the copper of his own blood. The pain throbbed, and Emory explored the torn skin with his tongue.

Even now, after more than a year of taking care of her, Emory could barely stand the sight of her. Sometimes he tried to tell himself this thing on the bed was not really her. Her soul had departed long ago, perhaps when she was first diagnosed. He recalled coming to the clinic on Wilson Avenue with her that

fateful day, reading an old issue of Newsweek as Mother went into an office with a counselor to get her results. They were both confident she had nothing to worry about, despite the night sweats and the low-grade fever.

Burned indelibly on his brain—the sight of the counselor opening the door to her office and Mother standing there, shaken, tears glistening in her eyes.

Now, maybe seeing his mother would be easier if she would stop deteriorating. Yet every day there was another lesion, purple and raised, eating her alive, faster and faster, insatiable in its hunger. Every day, Mother wasted away more; now her ribs were clearly defined; a skull grinned out beneath the stretched white skin of her face.

Illinois Masonic had an AIDS ward and they now admitted women, but Emory couldn’t do that to the woman who had raised him, who had loved and nursed him through his own myriad illnesses.

“Who the hell are you?”

There it was—her voice. It was still her voice. That was the amazing thing. This thing still sounded like Mother…the same velvety voice, tinged still with the accent of her North Carolina girlhood. Emory could still recall that voice reading him the story of The Poky Little Puppy when he was a child.

“Why, Mother, it’s your boy. Emory. You know that.” Emory shook his head, grabbed a towel and started to sop up the mess under his mother.

“I don’t have any kids! No boys! You asshole. I asked you who the hell you were, and you better think of something better than that before I call the police, young man!” Emory wondered where the strength came from that let her have such indignation as she wagged her finger at him.

He sighed. “Don’t you remember, Mother? Emory? Mary Helen?” Emory touched her forehead, brushing away a strand of straw-like hair from her face. Her forehead was hot, fevered demons racing around, consuming what was left of her brain. His palm grazed a Kaposi's lesion. It was raised and crusty, making Emory recoil. He wiped the hand that had touched her on his khaki pants.

Big Love

Big Love Blue Umbrella Sky

Blue Umbrella Sky The Man From Milwaukee

The Man From Milwaukee Unraveling

Unraveling Penance

Penance Husband Hunters

Husband Hunters Caregiver

Caregiver Superstar

Superstar Beau and the Beast

Beau and the Beast Obsessed

Obsessed Bigger Love

Bigger Love M4M

M4M I Heart Boston Terriers

I Heart Boston Terriers Dinner at Jack's

Dinner at Jack's A Dangerous Game

A Dangerous Game An Open Window

An Open Window Dinner at Fiorello’s

Dinner at Fiorello’s The Perils of Intimacy

The Perils of Intimacy Orientation

Orientation Dinner at the Blue Moon Cafe

Dinner at the Blue Moon Cafe High Risk

High Risk Sky Full of Mysteries

Sky Full of Mysteries Dead End Street

Dead End Street Crime Scene

Crime Scene Fugue

Fugue Blink

Blink Lost and Found

Lost and Found